Gold: Auri Sacra Fames

BY: BG EDITOR

THE NEW EL DORADO

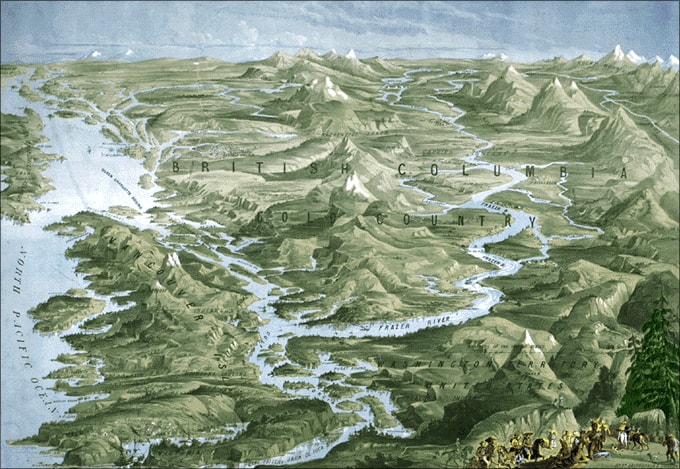

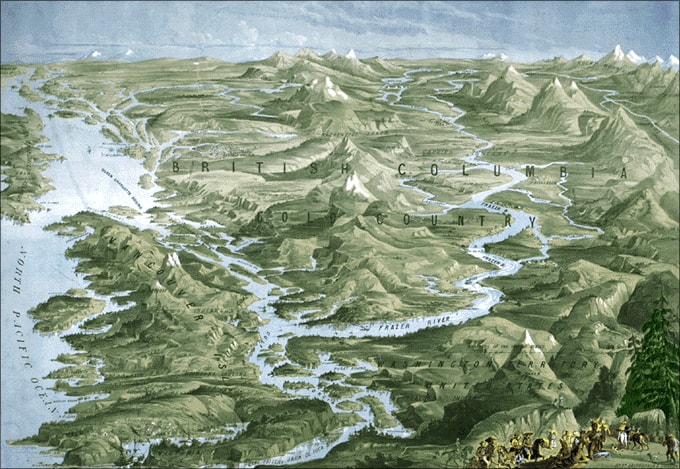

"A complete view of the newly discovered gold fields in British North America,

with Vancouver Island and the whole of the sea-bord from Cape Flattery to Prince of Wales Island"

Compiled from Authentic Views Plans & Charts in the possession of

Lieut. Charles Barwell, United States Navy

[ London, Pub. Sep 13th 1858 by Read & Co., 10 Johnson's C. Fleet St. ]

Dec 01, 2018 — GREENWOOD, BC (BG)

Greenwood's history during the Northwest's great gold rush is all the more appreciated when we hear about the daily life and challenges of the men and women who pursued buried riches. A History of British Columbia by R. Edward Gosnell [1] tells many stories about how the quiet lives of fur traders and residents of provincial forts were shaken up by the arrival of gold seekers, with their "insatiable auri sacra fames" [greed for gold].

Many of the stories of how people traveled to the various gold exploration 'hot spots' and how they worked their claims in the mid 1850's is very similar to the stories told of how gold and copper ore was pursued right here, around Greenwood.

"Gold is discovered. In 1857 a small party of Canadians set out from the boundary

fort of Colville to "prospect" on the banks of the Thompson and the Bonaparte. Other parties succeeded in making good strides, and immediately the news was in the air and soon a continent was inflamed.

Between March and June in 1858 ocean steamers from California crowded with gold seekers, arrived daily in Victoria. The easy-going primitive traders rubbed their eyes and sat up. Victoria, the quiet hamlet whose previous shipping had consisted of Siwash canoes and the yearly ship from England, in the twinkling of an eye found itself a busy mart of confusion and excitement.

In the brief space of four months 20,000 souls poured into the harbor. The followers of every trade and profession all down the Oregon coast to San Francisco left forge and bar and pulpit and joined the mad rush to the mines. It was as when the fiery cross was sent forth through the Old Land, men dropped the implements of their trade, left their houses uncared for, hastily sold what could be readily converted into cash and jumped aboard

the first nondescript carrier whose prow turned northward.

The motley throng included, too, gamblers, loafers and criminals, the parasite population which attaches to the body corporate whenever gold is in evidence; the rich came to speculate and the poor came in the hope of speedily becoming rich.

San Francisco felt the reflex action, every sort of property in California fell to a degree that threatened the ruin of the state. In Victoria a food famine threatened, flour rose to $30 a barrel, while ship's biscuit was at a premium. A city of tents arose, and all night long the song of hammer and saw spoke of rapidly put together buildings. Shops and shanties and shacks to the number of 225 arose in six weeks. Speculation in town lots reached an unparalleled pitch of extravagance, the land office was besieged before four o'clock in the morning by eager plungers and some wonderful advances are recorded.

Land bought from the company for $50 resold within the month for $3,000, a clay bank on a side street 100 feet by 70 feet brought $10,000, and sawn lumber for structural purposes could not be had for less than $100 per 1,000 feet. The bulk of heterogeneous immigration consisted of American citizens who strove hard to found commercial depots in their own territory to serve as outfitting bases for the new mines. It is not speculators, however, but merchants and shippers who determine the points at which trade shall center."

While many stayed in Victoria to exploit the growing miner community, the more adventurous among them pressed on, traveling up the Fraser toward the source of gold.

"The Fraser River begins to swell in June and does not reach its lowest ebb till winter; consequently the late arrivals found the auriferous ground under water. Thousands who had expected to pick up gold like potatoes lost heart and returned to California heaping execrations upon the country and everything else that was English. The state of the river became the barometer of public hopes and the pivot on which everybody's expectation turned, placer mining could only be carried on upon the river banks, and would the river ever fall?

A few hundreds of the more indomitable spirits, undeterred by the hope deferred which maketh the heart sick, pressed on to Hope and Yale, at the head of steamboat navigation, being content to wait and try their luck on the river bars there when at last the waters should fall. These intrepid men ran hair-breadth escapes, balancing themselves on precipice brink or perpendicular ledge, carrying on their backs both blankets and flour, enduring untold hardships, buoyed up only by the gleam of possible gold, that will-o'-the-wisp whose glamour once it touches the heart of a man spoils him for conservative work and till death comes leaves him never.

These determined ones pass through miseries indescribable, creeping long distances ofttimes on hands and knees through undergrowth and tangled thickets, wading waist deep in bogs and clambering over and under fallen trees. Every day added to their exhaustion; and, worn out with privations and suffering, the knots of adventurers became smaller and smaller, some dying, some lagging behind to rest, and others turning back in despair—it was truly a survival of the fittest, and here as elsewhere hopeful pluck brought its reward. At length the river did fall, and the arrival of the yellow dust in Victoria infused new hope among the disconsolate.

In proportion to the number of hands engaged on the placers, the gold yield of the first six months, notwithstanding the awful drawbacks of the deadly trails, was much larger than it had been in the same period in either California or Australia. The production of gold in California during the first six months of mining in 1849 was a quarter of a million. All the gold brought to Melbourne in 1851 amounted to a million and a half. From June to October, 1858, there was sent out of British Columbia by steamer or sailing vessel $543,000 of gold. But in this sum is not included the dust accumulated and kept in the country by miners nor that brought in by the Hudson's Bay Company or carried away personally without passing through banks or express office. It is a conservative estimate to declare that these last items would so augment the $543,000 as to bring it up to at least $705,000 for the first four months.

Yet this wonderful wealth was taken almost entirely from the bed of a few rivers, bank diggings being entirely unworked. A very small portion of the Lower Fraser, the Bonaparte and the Thompson, was the exclusive sphere of operations, the Upper Fraser and the creeks fed by the north spurs of the Rockies remained an unknown country.

The comparative figures of the gold yield were encouraging to those who thought, but much of the get-rich-quick element became disgruntled and returned to San Francisco, and the country was well rid of amateur miners, romantic speculators who built castles in the air and did neither toil nor spin, a spongy growth on the body politic. The stringent English way in which law was administered had no attractions for these gentry who fain would have re-enacted on British soil those scenes of riot and bloodshed which stained

California during the first years of its mad gold rush.

How Placers are Worked

To work placers one must have access to water, wood and quicksilver. In California mines water was very scarce, in New Zealand the early miners were hampered by the lack of wood for structural purposes. British Columbia had wood and water galore.

Arrived in the auriferous region, the miner must first locate a scene of operations, this pursuit is called "prospecting." Armed with a pan and some quicksilver the prospector proceeds to test his bar or bench. Bars are accumulations of detritus upon the ancient channel of some river; they constitute often the present banks of the river; benches are the gold-bearing banks when rising in the form of terraces. Filling his pan with earth the miner dips it gently in the stream and by a rotary motion precipitates the black sand with pebbles to the bottom, the lighter earth being allowed to escape over the edge of the pan. The pan is then placed by a fire to dry, and the lighter particles of sand are blown away, leaving the fine gold at the bottom. If the gold be exceedingly fine it must be amalgamated with quicksilver. Estimating the value of the gold produced by one pan, the

prospector readily calculates whether it will pay him to take up a claim there.

In this rough method of testing, the superior specific gravity of gold over every other metal except platinum is the basis of operations—the gold will always wash to the bottom.

Next to the individual "pan" comes as a primitive contrivance for gold washing, the

"rocker." This is constructed like a child's cradle with- rockers beneath, and is four feet long, two feet wide, and one and one-half feet deep, the top and one end being open, a perforated sheet iron bottom allows the larger pebbles to pass through, and riffles or elects arranged like the slats of a Venetian blind and charged with quicksilver arrest the gold. The rocker takes two men to work, one pours in the earth and the sluicing water, the

other rocks.

On a still larger scale is sluicing, which is really the same principle exactly as the pan and the rocker adapted to a powerful series of flumes or wooden aqueducts, down which some mountain torrent is deflected, the goldbearing earth being shoveled in from the sides. By means of an immense hose called a "giant," whole mountain sides of rich sand are broken down and subsequently treated. …

Placer mining is poor man's mining, and has a charm, a glamour of expectancy which yields to no elaborately planned out campaign of imported machinery, consolidated companies and the selling of shares. The free prospector, singly or in partnership, works off his own bat, makes his own discoveries and locations and hugs to his soul each night the delirious hope of millions on the morrow. Gold fever is a disease that the doctors cannot cure, and if its fiery stream courses through a man's blood for two or three successive years, no conservative position in the world with a certain salary fixed and limited will have power to hold him.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] A History of British Columbia by R. Edward Gosnell (1906), pg. 99